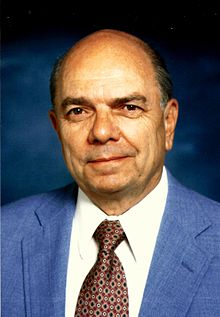

I learned a couple of days ago that Ken Davis, my friend, EFT colleague, and fellow trainer, has died. Here, in his honor and memory, I’m going to share some of my personal reflections on who Ken was and how I think he was important to me and to the development of Emotion-Focused Therapy.

Ken was instrumental in the development of Process-Experiential/Emotion-Focused Therapy research and training at the University of Toledo in the late 1980’s and through much of the 1990’s, and even into the early 2000’s. He had quite a bit of prior training in humanistic-experiential psychotherapies and co-led PE/EFT trainings with me. He was a natural group facilitator and often had to remind me to slow down and pay more attention to the relational processes in the group. Ken was a key member of the team at Toledo that developed an EFT approach to crime-related PTSD in the early to mid 1990’s, and he went on to help me run the Friday afternoon EFT training workshops that ran for years in the sometimes-challenging environment of the Psychology Department.

Based on these experiences and his interest in psychotherapy training, Ken was originally part of the writing team (with Jeanne Watson, Rhonda Goldman, Les Greenberg and me) for the first edition of Learning Emotion-Focused Therapy (APA, 2003). Unfortunately, his personal circumstances made it impossible for him to take part. (This was primarily due to the untimely death from breast cancer of his wife Deb and the subsequent demands of private practice and being the single parent of their young son.) However, his interest in training group process and on how students learn EFT is part of the DNA of the Learning EFT book and in EFT today. (See in particular the last chapter of the Learning book, where we discuss our understanding of what EFT training should look like.)

Ken was both a colleague and a friend. On the occasion of his 1992 wedding to Deb Smith (who was the great love of his life), I wrote the following little poem:

Flocking of flamingos

emergent property

as each one follows desire of heart

to take wing together.

For his PhD dissertation, Ken took on the challenging task of developing a measure of therapist response modes in EFT, analyzing a collection of significant therapy events identified by clients in the Toledo Experiential Therapy of Depression project. Probably his most interesting finding had to do with content directive responses, like advice-giving and interpretation. He found that on average EFT therapists used these responses about 1% of the time, that is, about one per session; nevertheless, these therapists were clearly doing EFT. However, one of the therapists in the study used these responses about 5% of the time, and it was quite clear that they were not really doing EFT at all. Ken colorfully described this therapist as “a CBT wolf in process-experiential sheep’s clothing.” I still tell this story today when I cover the EFT therapist response modes in trainings.

Over the past two years I’ve numerous occasions to look things up in Ken’s dissertation as part of various recent projects. If you are interested in learning more, here is the citation and a link that I hope will take you to more information about it:

Davis, Kenneth L. (1994). The role of therapist actions in process-experiential therapy. University of Toledo, Department of Psychology.

In all my many moves over the past 18 years, I have lost track of the data set Ken used for this study, so about a year ago I reached out to him to see if he still had the transcripts and recordings from his project. I thought this might be a nice excuse to reconnect with him. He eventually said that he thought data was around somewhat but he wasn’t sure where and was having trouble getting around to try to locate it.

I’m not sure whether my reaching out to him had anything to do with it, but I was delighted when Ken signed up for one of my zoom-based Advanced Empathy Attunement trainings last August through the EFT Institute of Southern California, organized by Lada Safvati. I don’t think that he really needed the training, but when asked why he signed up, he said it was fun for him to revisit EFT and see what is happening with it today. He told me that he had a neuromuscular disorder that had really slowed him down, but even so it was lovely to see him. After that, together with his sister Carla (who is currently studying counselling), he signed up for the Level 2 that Ladan and I ran in December. However, I think he was not well enough to participate, because he had to withdraw after a day or two. The last time I saw him was the first day of that training.

I remember Ken as gentle, wise, funny, kind, determined, and as deeply grounded in the body. He was trained in massage and worked with folks with neuromuscular conditions. I remember how one time when someone said they were having back trouble, he got down on the ground, analyzed their stance, and offered a set of useful suggestions. I remember another time when he and I had him put his allergies in a chair and have a dialogue with them. Certainly, working with him gave me more appreciation for the bodily dimension of EFT, so I think that’s another influence he’s had on the development of EFT.

I also remember how he supported me while I was having a hard time with some colleagues in the Psychology department, as our relationship evolved from student-professor to colleague-friend. And I remember how in the early days of managed care he used to complain about poorly trained staff mis-managing psychologists who were working with complicated, fragile clients who needed more than 10 sessions of CBT.

Burned into my memory are also images of him and Deb and their son Josh, and then him and Josh at Deb’s memorial service. So in looking through the remembrances on his Tribute Wall it was especially poignant to see the photo of Ken, wearing his academic regalia, hooding his son Josh at Josh’s graduation with a doctoral degree in Physical Rehabilitation. (I love the legend at the bottom: Hooder: Dr. Father. Kenneth Davis).

So I’m left with a set of memories of our time together running EFT trainings when it all felt new and sometimes like we were making things up as we went along. It was an exciting and challenging time, and I am grateful to have had Ken’s company through much of it. I’m also left with some regret that we weren’t able to do more together, for all the time of being disconnected after Diane and I moved to Scotland in 2006, and for not expressing to him the extent of what he meant to me.

In our time together, Ken and I published two book chapters together on the crime-related PTSD study. I’ve listed both below, with links to versions of them listed after each. The first one is only available in a pre-publication version, while for the second one there is a photocopy of the published version:

Elliott, R., Suter, P., Manford, J., Radpour-Markert, L., Siegel-Hinson, R., Layman, C., & Davis, K. (1996). A Process-Experiential Approach to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In R. Hutterer, G. Pawlowsky, P.F. Schmid, & R. Stipsits (eds.), Client-centered and experiential psychotherapy: A paradigm in motion (pp.235-254). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang.

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/a67k8zf739ac7v1lc4sw2/PTSDEXP_994.docx?rlkey=bez558e2uj626h3o8n6zvs88f&dl=0

Elliott, R., Davis, K., & Slatick, E. (1998). Process-Experiential Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Difficulties. In L. Greenberg, G. Lietaer, & J. Watson, Handbook of experiential psychotherapy (pp. 249-271). New York: Guilford. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/r3plx64nw1fil9u6379zr/Elliott-Davis-Slatick-1998-EFT-for-Crime-Related-PTSD.pdf?rlkey=ncw8wnd453m1fndfkfug39f34&dl=0

Fare thee well, Ken: my old friend and colleague. Your kind, compassionate, gentle spirit lives on in EFT today, and exemplifies what is best about it!